SEARCH THE WEBSITE

Timothy Soar

The new facade of 8 Finsbury Circus in London (center building) by WilkinsonEyre; Britannic House by Sir Edwin Lutyens to the left.

Stanhope, the developer on behalf of the client Mitsubishi Estate, wanted the project to attract a 21st-century clientele interested in prime Class A office space, hence the contemporary architectural language. This also motivated WilkinsonEyre to bring some interest, as well as natural light, to the center of the deep floor plate. With all of the air handling equipment located in the basement, the building’s design had to include an airshaft. But rather than make this a blind void, the architects decided to expose the open air space and fill it with an artful and intriguing design feature. To help bring all the elements together and make it work, they hired Carpenter Lowings.

“We have known WilkinsonEyre a long time,” says Luke Lowings, co-founder of Carpenter|Lowings and lead designer on the project. “We had recently done a design with them on a building that didn’t get built, where we used a rippled surface to get light into a slender courtyard. I think that design came to mind when they [WilkinsonEyre] were thinking of what to do with this airshaft.” And so, as is often the case in architecture, one built work’s origins are born out of another project’s unrealized design.

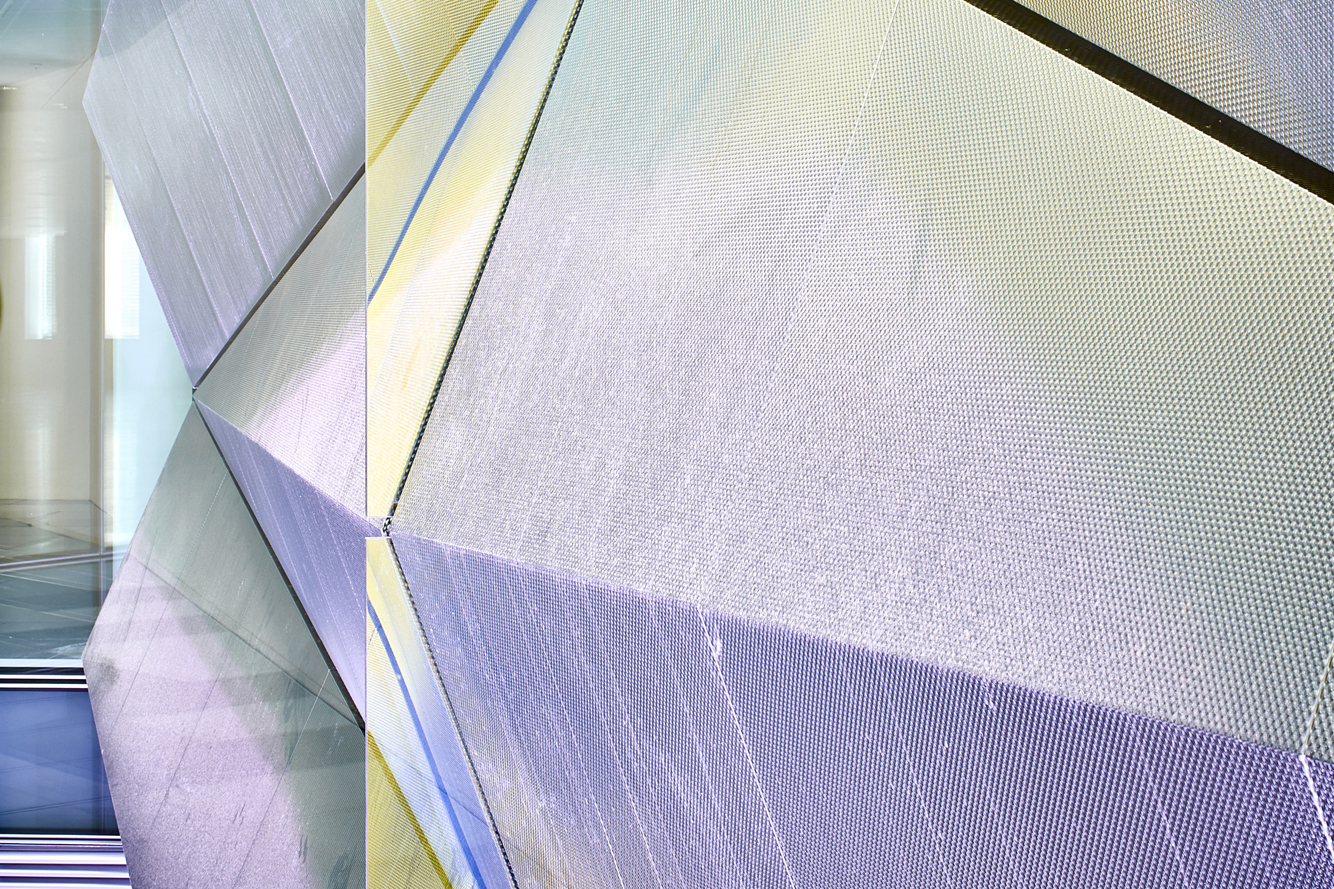

For the Finsbury Circus installation–it measures 40-meters-high (131.2 –feet-high)–the artwork’s rippled surface is composed of 47 three-dimensional forms comprised of 217 laser-cut stainless-steel panels, each 1.2mm-thick (0.047-inch-thick), with a dimpled mirror finish. The panels, mounted onto welded aluminum frames, are folded at 90 different points, creating an accordion-like surface across the elevation of the installation, with the upside of the folds catching and reflecting what daylight enters from the top of the shaft. The gaps in the joints of the panels, run perpendicular to the line of the fold. The joints in the surface allow viewers to “read the actual making of the thing, as well as the light idea,” says Lowings.

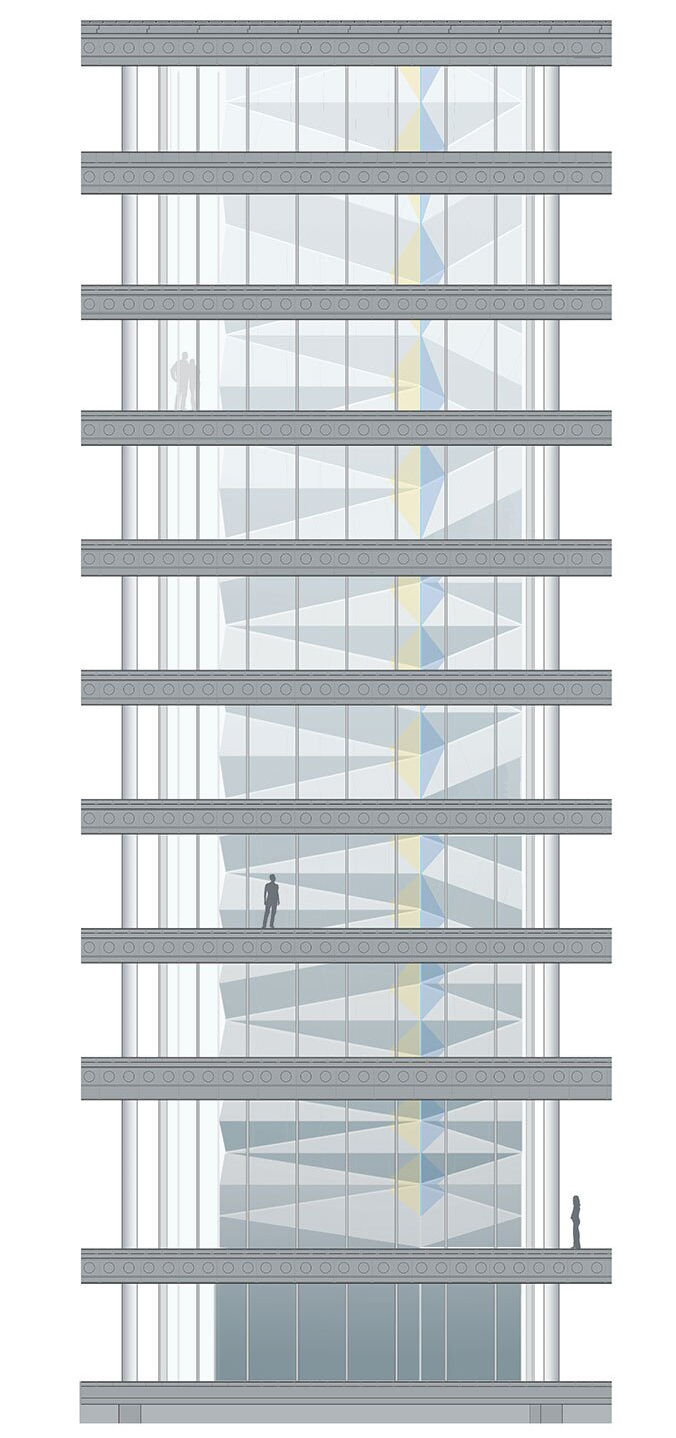

Elevation (top) and plan (bottom) of "Folded Light" show how the installation sits in the building's air shaft.

The folds are more compressed and deeper at the bottom of the artwork, and more open and shallower at the top of the piece. “We took the position of maximizing the perception of light, rather than the quantity of light,” says Lowings. “Unless you’re tipping light into a space, you can’t get more than what comes through the top. We considered a heliostat to tip light in, but couldn’t go higher due to planning regulations. Folding the panels more tightly toward [the] bottom lead to an angle that reflects the light from higher up.”

Elevation of the installation "Folded Light"

In creating the installation, Carpenter|Lowings had some concerns that “Folded Light” would not read as a continuous sculptural element when viewed in sections, from floor-to-floor. They worried that it would seem out of scale. So, to create a sense of visual continuity, bridging floors from top to bottom, Carpenter|Lowings added a 12-millimeter-thick (0.47-inch-thick) blade of dichroic glass that measures 36.5-meters-long (119.7-foot-long) and asymmetrically bisects the elevation. The glass is comprised of “14 separate laminated and dichroic coated elements,” and reflects golden light and transmits indigo, enhancing the experience of what daylight does enter the shaft. The result is a poetic representation of the natural world’s blue sky and yellow sun.

Since available daylight in the shaft was limited, especially on gloomier winter days, the design team, which included lighting consultant EQ2 Light, included supplemental electrical lighting. At the top, around the skylight, are eight 139W medium beam RGBW LED projectors tuned to resemble the color temperature of natural light. At the bottom of the installation are eight additional 139W medium beam RGBW LED projectors that uplight the piece. These are color-changing fixtures. Carpenter|Lowings set them to indigo, though the controls are in the hands of the building management and can be programmed however they wish with tenant input. To provide sidelight, 3000K medium beam LED linear projectors, which provide 20W per meter are installed at every level, painting the stainless steel surfaces with the colors created by the white light’s interaction with the dichroic glass blade.

Whether natural or simulated, “Folded Light” delivers the dynamic experience of daylight to the center of its host building. But it does more than that. It also serves as a unifying element for a structure that might otherwise have read as a series of disconnected floors. “It’s not a particularly big office,” says Lowings, “but there in the middle of the floor you become unaware of daylight. This [“Folded Light”] provides that awareness. It bridges floors and connects the building vertically. It’s more sculptural than decorative—not meant as a pretty pattern, but as a strong statement that makes you aware of the scale of the building.”

Project Name: “Folded Light,” 8 Finsbury Circus, London